The rich are getting ridiculously richer. But Karl Marx would have told you to expect that. It’s embedded in the very nature of capitalism.

Billionaire wealth has increased by 81% since 2020 and risen by over 16% in 2025 alone, reaching a record $18.3 trillion. Marx believed that wealth would concentrate at the top leaving most of the population in misery.

However, since the late 19th century, some have argued that Marx was wrong because the poor got wealthier in absolute terms, even if the wealth gap had increased. In the post-war period it was often stated that trade unions, the welfare state, and better regulation had rendered Marx’s analysis of capital accumulation obsolete.

Strange to say, it might be making a comeback. Because not only is the gap between rich and poor now a yawning divide, but people are increasingly unable to afford basic goods and services. The debate around affordability and the cost of groceries in Trump’s America is a good indicator of this.

In the 1960s, the top 1% of earners owned 8% of American wealth. Today, the richest 1% in the United States own a quarter of national wealth and own 40% of the economy. In the early 20th century, under President Theodore Roosevelt, the administration actively ‘bust’ trusts to half increasing monopolisation. There is no evidence that is on the cards today.

Capitalist economist observe the trend early on

Marx’s observation that capital finds its way into fewer and fewer hands was also noted by capitalist economists like Adam Smith and David Ricardo – to whom Marx always acknowledged an intellectual debt. Smith called it a ‘monopolising spirit’ with merchants and manufacturers always plotting to choke off competition and act against the public interest.

Smith wrote that “for one very rich man, there must be at least five hundred poor, and the affluence of the few supposes the indigence of the many”. While Smith had enormous confidence in the power of capitalist competition to resolve most problems, he implicitly supposes that on occasion, regulation would be needed to ensure the trend towards monopoly was checked.

The Marxist view of capital concentration

The concentration of capital is a fundamental, inherent process of the capitalist mode of production, driven by competition and the relentless pursuit of profit (surplus value). It refers to the accumulation of financial resources, means of production, and economic power into fewer hands, resulting in larger, more dominant enterprises

Capitalists are driven to constantly reinvest their surplus value (profits) into new, more efficient, and larger-scale production methods. Marx summarized this as: “Accumulate, accumulate! That is Moses and the prophets!”. Competition forces capitalists to lower production costs to survive. This requires investing in new technology (increasing constant capital) and achieving economies of scale.

Larger, more efficient firms can produce goods cheaper and sell them at lower prices than smaller competitors, driving smaller firms into bankruptcy or forcing them to be absorbed. How does capital concentration happen in practice? As technology advances, capital invested in machines, raw materials, and technology (constant capital) grows much faster than the investment in labour (variable capital).

This trend leads to the creation of a “relative surplus population” or “industrial reserve army”—a pool of unemployed workers whose competition forces down wages.

Bankers also play a role as they act as “general managers” of money capital, allowing them to channel resources toward the largest, most profitable enterprises, further centralising control over the social capital.

All of this leads to monopoly capitalism with the domination of monopolies, which, in the era of imperialism, begin to control both domestic and global markets. As capital concentrates, the productive forces expand faster than the market can absorb goods (due to the restricted consumption of the working class), leading to regular, increasingly severe crises of overproduction.

Marx argued that this process creates the preconditions for its own destruction. By concentrating production into massive, socialised units, it sets the stage for the working class to seize control of the means of production—the “expropriation of the expropriators”.

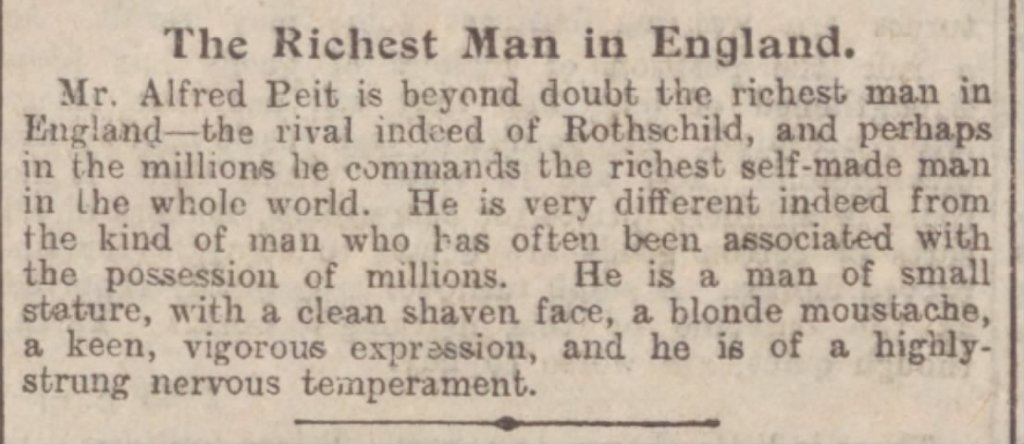

In 1903, the richest man in England was Alfred Beit (1853-1906), an Anglo-German gold and diamond magnate whose fortune was made in British-ruled South Africa and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) during the Boer War. At his death, aged just 53, he left an estate worth £8,049,886 (equivalent to £1.05 billion today). That would be peanuts compared to the richest billionaires in the world in the early 21st century.

Categories: Economics

Leave a comment